Traveling to a foreign country whose language isn’t alphabetical is never easy. Just imagine the challenge of typing down a street name in Google Maps! Asking the locals for directions will surely be another struggle. Fortunately, that’s something you don’t have to worry about if your destination is Vietnam.

Vietnamese has a Latin-based alphabet, making it similar to Western languages. You will likely not have any problem copying addresses and booking ride services even though you may not speak the language. But the Vietnamese language wasn’t always like that. Its somewhat modern appearance is the fruit of a long and difficult journey as it accompanied Vietnamese people through a history filled with upheavals and rivalries as well as intrigue and prosperity.

At first glance, the Vietnamese language appears to have many close resemblances to Chinese in both its lexical system and phonological rules. Seventy percent of the Vietnamese vocabulary has Chinese origin (Cao Xuân Hạo, 2001), making up what is known as the Hán-Việt lexicon. Examples of Hán-Việt words are thân thể (body), phòng (room), hạ (summer), etc. These words are used just as widely as the native Vietnamese vocabulary. Their pronunciation also systematically relates to the Chinese equivalents. As a result, it’s not surprising that many linguists believe Vietnamese to be a product of the Chinese language. In 1830, J. L. Taberd (a priest and appointed missionary in Cochinchina, modern Vietnam) improved upon the works of earlier priests and lexicographers, namely Alexandre de Rhodes and Pigneau de Béhaine, and published his own Vietnamese-Latin dictionary called Dictionarium Anamitico-Latinum. In this work, Taberd suggested that Vietnamese was actually a degenerated version of Chinese. From this point of view, Vietnamese should be considered part of the Chinese language family.

However, a closer look at the Vietnamese lexical system reveals that the massive Hán-Việt lexicon mentioned above, while substantial, consists only of loaned words. Indeed, Hán-Việt vocabulary is primarily a cultural lexicon – separate from the core lexicon of the Vietnamese language. This reveals that despite heavy Chinese cultural influence, Vietnamese retained their linguistic independence, only borrowing vocabulary where needed rather than being wholly assimilated. Some frequently used Hán-Việt words appear to belong to the core lexicon. However, the number of such cases isn’t significant, and the associations between those words and their Chinese equivalents often lack systematicity. For example, the word đầu (head) might have originated from the Chinese word 头. But within the same system of basic vocabulary used to denote similar organs, there are no Chinese equivalents with such phonological resemblances for mắt (eye), mũi (nose), or tóc (hair).

Ancient Chinese documents tell a similar story. According to the Book of The Later Han (后汉书), a 5th-century history book written by the famous Chinese historian Fan Ye (范晔 ), during the first century, people living in Giao Chỉ (the former name of what would become Vietnam) and the people in the Central Plain (a large part of what would become China) spoke different languages. To communicate, they required multiple translators, indicating that Vietnamese and Chinese are unlikely to have the same origin. Grouping Vietnamese together with Chinese, thus, proves to be a weak argument from the viewpoint of comparative-historical linguistics.

The origin of the Vietnamese language has long been a controversial debate. However, most prominent scholar linguists such as A.G. Haudricourt (1953), S.E. Yakhontov (1973), and M. Ferlus (2001) agreed that Vietnamese belonged to the Mon-Khmer language branch of the Austroasiatic family. More specifically, Vietnamese was a major part of the Vietic group within the Mon-Khmer branch. From there, the language gradually evolved and differentiated as people left the Northern Mountains, traveled to the Southern plains, and eventually inhabited the Red River Delta – the heart of ancient Vietnam. During that time, the Vietnamese lacked an official writing system, leaving limited records and fueling controversies around the language’s origin and history. The thousand years of Chinese domination (111 BC – 939 AD) appear to make it even harder for linguists to establish a clear historical profile of Vietnamese as an independent language. However, the persistence of Vietnamese despite cultural assimilation efforts underscores its resilience as a distinctly Vietnamese language.

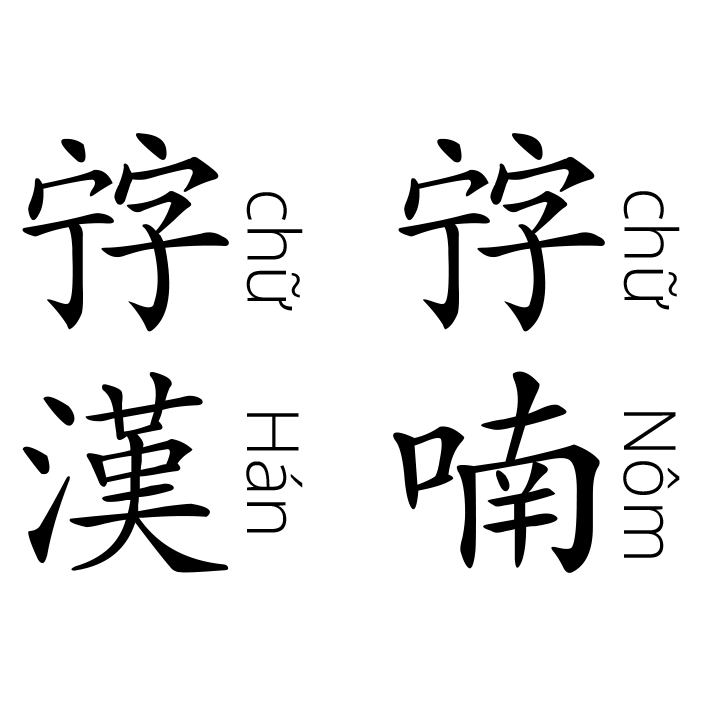

As the Chinese ruled over ancient Vietnam, the Chinese language and writing system was adopted as the official language for educational and governmental duties. Despite such attempts at cultural assimilation, the Vietnamese language persevered with its people. There was never a point in history when the Vietnamese people ceased speaking in their mother tongue. Classical Chinese and Vietnamese co-existed in Vietnam for centuries, nearly the entire length of Chinese domination in Vietnam (Nguyễn Tài Cẩn, 1998).

In an effort to resist the Chinese influence and preserve their culture, the Vietnamese people developed their very first writing system called Chữ Nôm. After years of research, Vietnamese linguists have come to an agreement that Chữ Nôm became a functional writing system approximately in the tenth century, although a large part of its vocabulary might have been coined long before.

In the first stage, the Vietnamese people adapted Classical Chinese, using it to spell out native Vietnamese names, lands, plants, animals, and other items. This stage might have started as early as the first century AD, with much of the vocabulary coined during the sixth century.

In the second stage, in addition to spelling native concepts, Classical Chinese was also employed to form new written words. There are several methods: Chinese characters were borrowed and marked with diacritics indicating phonological features. Or, a native word was written using a Chinese character with a similar sound, regardless of meaning. Another way of coining new words was to combine two Chinese characters, one to indicate meaning and the other to indicate sound. In some cases, the original Chinese characters were simplified by removing a few strokes to make new Nôm words. This showed an effort to mold foreign writing to the Vietnamese language rather than fully conforming to the Chinese system.

In the early stages, Chữ Nôm was used mostly to translate Buddhist scriptures from Chinese. Gradually, it gained popularity, becoming the language of choice for literature, medicine books, and Confucian texts. Chữ Nôm rose to its peak between the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1867, Nguyễn Trường Tộ, a scholar and reformist during the Nguyễn Dynasty rein, proposed standardizing Chữ Nôm to Emperor Tự Đức. His concern stemmed from the fact that a single Vietnamese word had various Nôm representations. For example, the word chữ (meaning character or text) could be written as either 字, 𡦂, or 𡨸. This not only made chữ Nôm difficult to read and learn but also led to discrepancies in manuscripts, as scribes couldn’t reliably distinguish Nôm characters and ended up copying them inaccurately. Unfortunately, Nguyễn Trường Tộ’s proposal was ultimately rejected, leaving Chữ Nôm unstandardized.

When Catholic missionaries arrived in Vietnam during the 16th & 17th centuries, they needed to translate religious texts to the native language to begin evangelization efforts. Although Chữ Nôm aided their mission initially, it proved less than ideal. Understanding Chữ Nôm required literacy in Classical Chinese, which at the time was limited to the elite and the privileged due to the cost of education. To reach a broader audience, the priests knew they needed a standardized and easy-to-learn writing system.

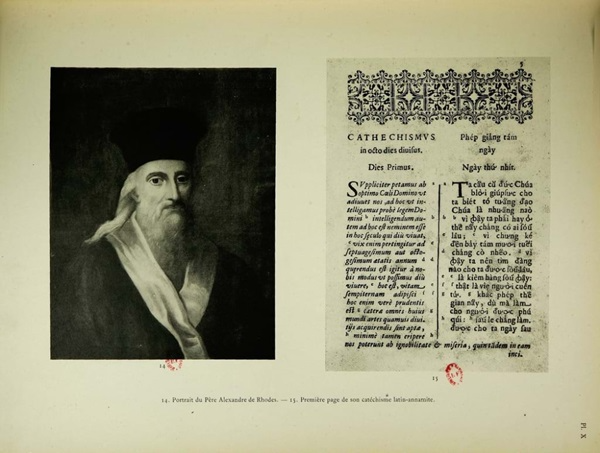

French Jesuit lexicographer Alexandre de Rhodes is usually who comes to mind regarding the Latin-based writing system known as chữ Quốc Ngữ (national language) of Vietnam. A street in central Ho Chi Minh City, a major Vietnamese economic hub, was even named after Alexandre de Rhodes as a token of gratitude for his invaluable contribution. However, he wasn’t solely responsible for developing the Vietnamese Latin alphabet.

In fact, the Romanization of the Vietnamese writing system was a collaborative effort among several Catholic missionaries. Portuguese Jesuit Francisco de Pina did much of the initial groundwork. Building upon Pina’s foundation, fellow Portuguese Jesuit Gaspar do Amaral developed a Tonkinese-Portuguese dictionary, while António Barbosa worked on a Portuguese-Tonkinese equivalent (Tonkin being the French colonial name for northern Vietnam). Unfortunately, all three passed away before finalizing their work. Alexandre de Rhodes picked up where his predecessors left off, systematizing everything into the Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum, the first trilingual Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin dictionary (published 1651 in Rome). In the prologue, de Rhodes gave credit to all three predecessors.

Despite the advantages of this Latin-based writing system, Vietnamese people were understandably suspicious due to its colonial heritage and religious purpose. Thus, they continued shunning it for another century or so.

On January 1st, 1882, the French colonial government issued a decree enforcing the use of chữ Quốc Ngữ in all official government activities. This met resistance, as natives still considered the Romanized alphabet the property of their enemy. Native Vietnamese didn’t want to learn this new writing system for fear of losing the essence of their culture – their souls. As a result, the colonial regime forced young children into schools specifically teaching chữ Quốc Ngữ. Well-off families countered by having servants pretend to be their children and attend instead. The educated class fought back even harder. Polemical wars dragged on among scholars in southern Vietnam, notably between poet Phan Văn Trị (who opposed the enforcement of chữ Quốc Ngữ) and scholar Tôn Thọ Tường (a Catholic who supported the French regime). Such heated scholarly debates reveal the cultural significance of language and the perceived threat chữ Quốc Ngữ posed to Vietnamese identity.

Under the government pressure, resistance proved futile. By 1879, chữ Quốc Ngữ had become the standard for education. From that point onward, it was no longer solely Catholic property. Chữ Quốc Ngữ truly earned its place as the national language, enabling mass literacy and education. Reading and writing were no longer something reserved for the privileged. Recognizing chữ Quốc Ngữ’s potential to empower people and progress the country, in 1907, Vietnamese scholars Lương Văn Can, Nguyễn Quyền, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, and Phạm Duy Tốn opened Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục, an institution offering free public education (Nguyễn Thìn Xuân, 2007). Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục taught chữ Quốc Ngữ, French, and Classical Chinese with a focus on practicality. Subjects included History, Vietnam Geography, Mathematics, Arts, and Science. The teaching of history and geography, in particular, promoted a modern view of nationhood, countering colonial boundaries with a Vietnamese-centered worldview. They also introduced tales of famous international politicians and activists, which were warmly received by all students. Besides the academic activities, Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục promoted generosity, solidarity, and patriotism while dismissing superstitions and outdated traditions such as men growing long hair and wearing it in a bun or people dying their teeth black (Nguyễn Hiến Lê, 1956).

Threatened by the influence of Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục, the colonial regime shut it down after just one year. Despite its short existence, Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục left a huge mark on the country’s progress, spurring Vietnamese activists and sparking other civil movements. Picking up where Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục left off, Vietnam’s Communist Party offered basic education (chữ Quốc Ngữ and Mathematics) to the working class. Rather than rigid textbooks, teachers crafted simple rhymes to facilitate learning, like “O tròn như quả trứng gà. Ô thì đội nón, Ơ thì thêm râu” (O is round as an egg. Ô wears a hat, Ơ has a mustache.). To this day, older generations fondly remember these spelling verses.

For the Vietnamese people at the time, learning chữ Quốc Ngữ was about more than literacy. It also served as a means to instill virtues in young children and adults, steering them away from destructive acts like gambling and drinking that were very common back then. Along with chữ Quốc Ngữ, people learned about the importance of solidarity and patriotism, leading them to join the resistance against foreign influence. Throughout the long war with the French, spreading chữ Quốc Ngữ remained a priority because it was seen as the path to progress and freedom. History proved them right.

It’s been over 140 years since chữ Quốc Ngữ was mandated. From seeming like an outsider’s language to becoming the nation’s official writing system, chữ Quốc Ngữ has had its fair share of twists and turns. While created by the Portuguese and French Catholic missionaries, it was the Vietnamese people who embraced and popularized chữ Quốc Ngữ, making it part of Vietnam’s identity. This allowed chữ Quốc Ngữ to fulfill the Vietnamese desire for a writing system that represented their independent national identity, separating them from the Chinese writing system of their colonizers.